Part 1 - How To Write

Since January 16, 2021, I’ve wanted to write publicly, but for four years I struggled. Several times I opened a Google Doc to write, but it left me discouraged. The words didn’t flow, they sounded clunky, and I gave up several times.

The issue is I wasn’t writing consistently. And when I did, my writing was so dry and inauthentic—like reading from a textbook—that it discouraged me from continuing.

Now, six months into writing daily—and 45,000 words written—I’ve learned the missing ingredient holding me back from writing well: knowing how to write and how to connect ideas.

“Writing a first draft is very much like watching a polaroid develop. You can’t—and in fact—you’re not supposed to—know exactly what the picture is going to look like until it has finished developing.” — Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird

Why Write

(i) If you want to write well, you can. I’m a former college football defensive lineman, up to my neck with CTE, and I learned how to write. So can you.

(ii) The central theme of Ben Franklin’s life was progress: the idea that individuals and humanity improve based on a steady increase of knowledge. I share this opinion. I also believe I have a responsibility to contribute in some way to make my small part of the world better.1

(iii) Everyone has a unique story to tell. Told well, you can inspire others and uncover untold truths within yourself that hadn’t been crystallized until putting it down on paper.

I’m far from an expert, with plenty of room for improvement. But after four years of trial and error, I’ve found a process that works for me—using tactics from some of the brightest minds of the last few centuries.

Writing Consistently

Anne Lamott has published twenty books and has led writing workshops for almost three decades. She understands the mental blocks that new writers—like me—go through.

This is her best advice that helped me:

Start Small: Chunk your writing into the most bite-sized piece. Don’t write a whole book—or even an essay—just get one thought down on paper at a time. Your essay will take form over time, like watching a polaroid develop.

Be Consistent: The best writing advice is to write more often. Try to sit down to write at the same time every day. This trains your mind to become creative at that particular time each day.

Write Honestly: You'll know you're writing honestly when it feels as though the right words were already inside you waiting to be freed onto paper. When you get inspiration from personal observations, it’s probably a universal truth.

Few writers know what they’re doing until they’ve done it. Even if your draft feels sloppy, just get something, anything, down on paper, and you can wordsmith it later.

James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, has his own advice that helped me consistently write. He advises you to ask yourself, “What can I stick to even on my worst days?”

I write 250 words—one paragraph—a day. Even if you’re just getting started, you can write one paragraph a day. When you do get started, you might find yourself in a flow, writing more than you originally planned. Starting is the hardest part.

Part 2 - How To Connect Ideas

Once I finally got into the flow of writing, I loved it. Almost like journaling, but on my computer, and for an audience of three readers.

I wanted to write genuinely useful, well researched essays that help others live better. What I needed was a better way for capturing ideas over time.

“No matter how internal processes are implemented, (you) need to understand the extent to which the mind is reliant upon external scaffolding.” — Neil Levy

The challenge with writing well researched essays is recalling facts from many different books.

In his book How To Take Smart Notes, Dr. Sönke Ahrens remarks that experts across domains universally agree that deep thinking requires some kind of external scaffolding to connect ideas together.

You need to scaffold your thoughts because your brain has limited ability to recall bits of information when needed.

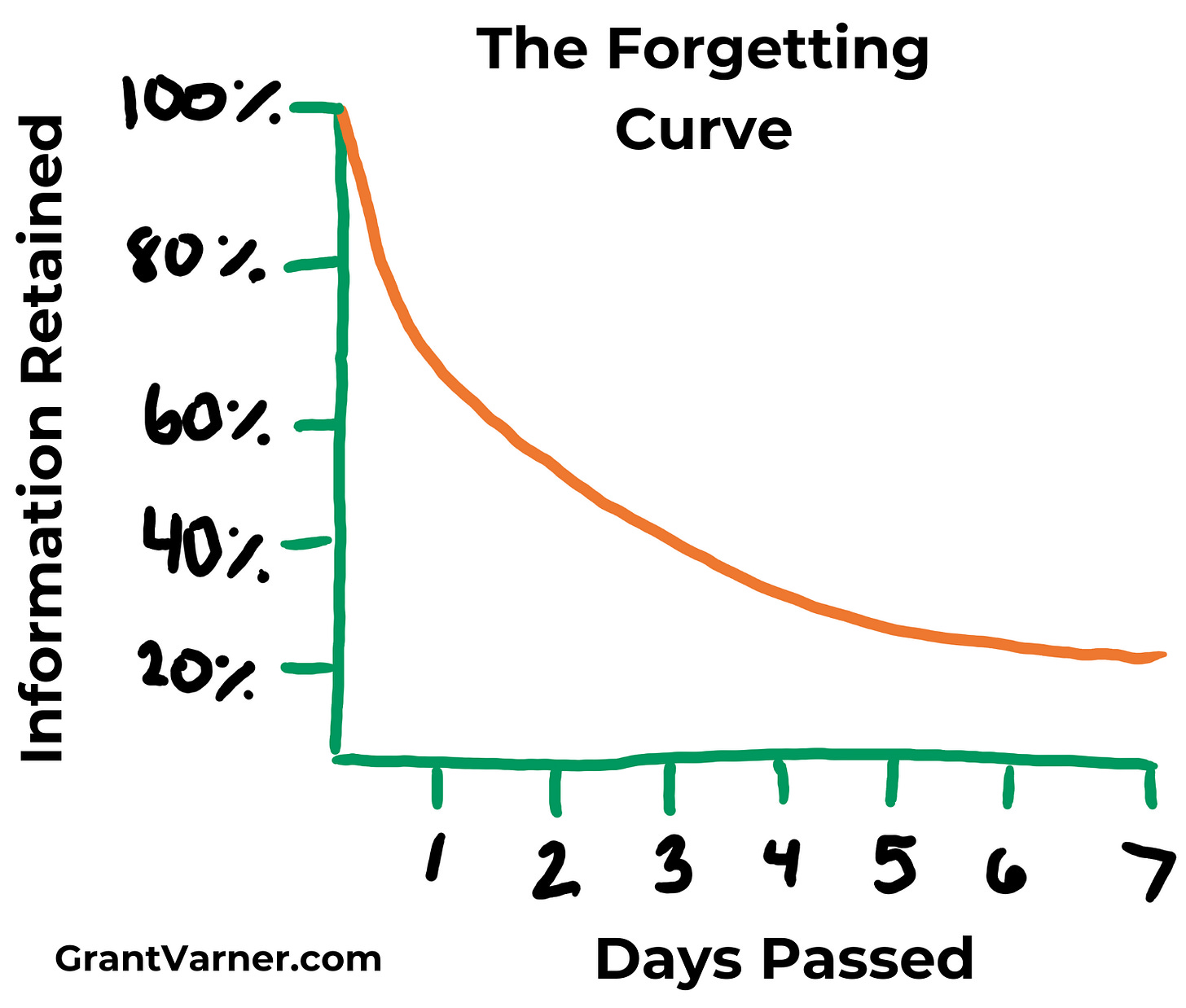

The forgetting curve, theorized by German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885, illustrates how quickly information is forgotten.

The forgetting curve postulates that people can forget up to 50% of new information within an hour, and 70% within 24 hours. After one week, people may forget up to 90% of what they learned.

Information Capture

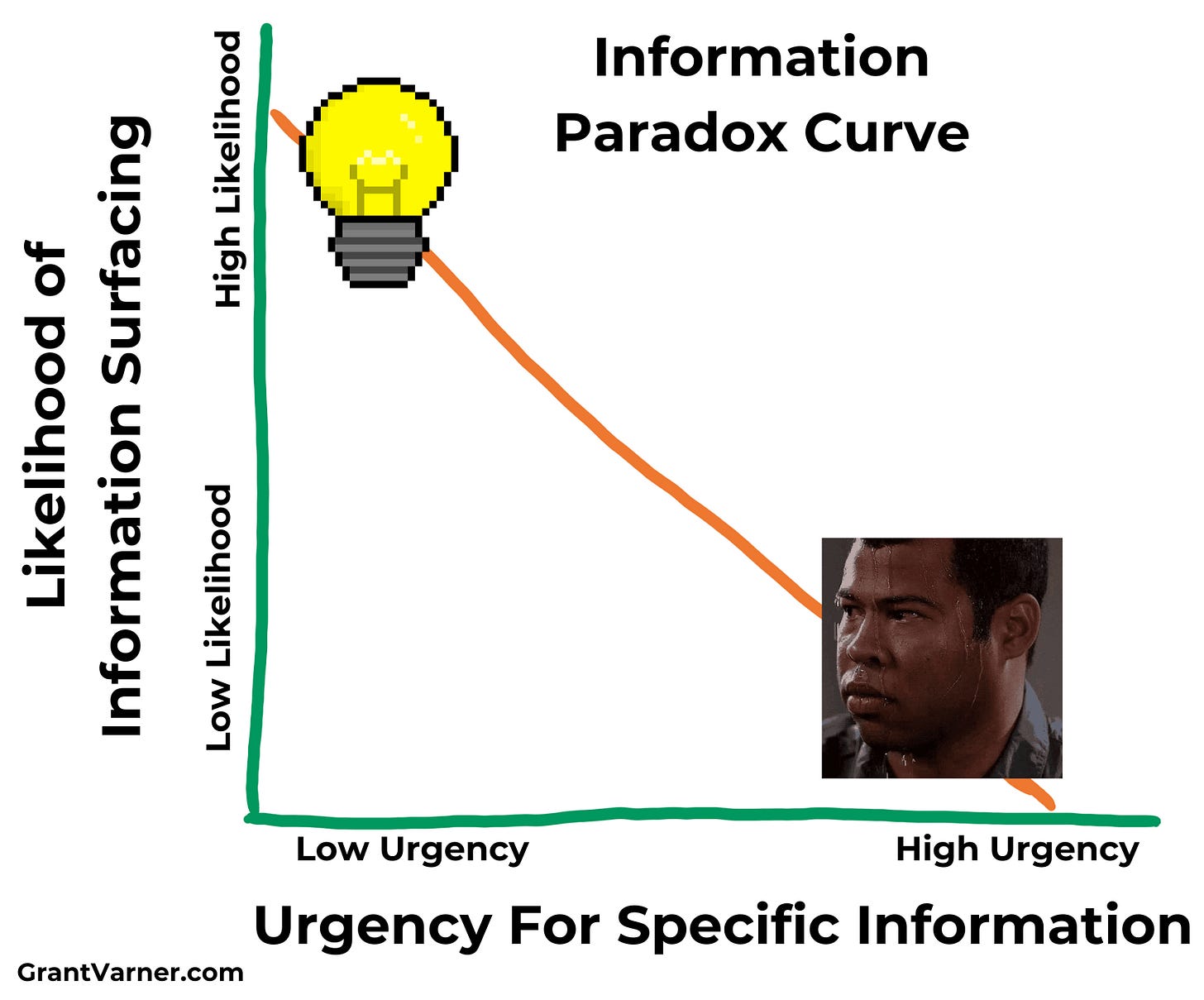

Due to the forgetting curve, you rarely recall information the exact information needed when you need it. More often you come across those ideas when you aren’t expecting it—days, weeks, even months before you ever need it for an essay.

To mitigate the effects of the forgetting curve, I use my iPhone Notes app to capture notes whenever I come across great information in the wild.

Proactively capturing great information when it appears come up will level up your ability to create well researched writing.

Idea Synthesis

Now that you’ve begun capturing good information, you need to synthesize them.

Once in a blue moon I’ll flip through my notes, and cut/paste the many random thoughts, and bits of information into logically organized groups. After some time of doing this, the structure of an essay begins to take shape.

“Thinking, reading, learning, understanding and generating ideas is the main work of everyone who studies, does research or writes. If you write to improve all of these activities, you have a strong tailwind going or you. If you take your notes in a smart way, it will propel you forward.”

—Sönke Ahrens

Isaac Newton, one of the most accomplished thinkers our time ran this playbook to a T.

Isaac Newton’s Notes

Though he was alive in the 1600’s, Newton used many techniques that Sönke Ahrens later formalized in Smart Notes.2 Surviving books from his library show that Newton would take extensive notes in the book itself, often filling entire margins.

(Skip ahead to 0:36 for Isaac Newton’s early notebooks.)

Idea Capture: Newton’s notebook was meant for jotting down observations. Coincidentally, his notebook was about the size of an iPhone, using it similarly to how scribble ideas and information into Apple Notes.

Idea Synthesis: He synthesized his ideas often. This allowed him to quickly retrieve and connect ideas—scaffolding information outside his brain—that he could bring back into his research.

Newton’s natural curiosity also helped. One article notes that Newton’s wide-ranging interests and ability to mix and combine information from different fields helped him achieve massive breakthroughs.

How I Take Notes

When I was a kid I used to love freeball building cool things with legos, without instructions using the pieces I already had. Writing this essay was a bit like that. This is a play-by-play of how I wrote a recent essay.3

Several weeks ago I was doing some travel for work, still trying to write daily, workout, and be fully present with my wife. When I realized my struggle, I pulled out my iPhone and jotted into my Notes app: “Struggling to get everything done each day. Is there a better way to get more done in less time?”

Several days later, I stumbled upon this older post by Sahil Bloom, which covered telic vs. atelic activities. Atelic activities seemed perfect to add about being able to unwind to make the most of the time with my wife.

By this point, I felt like I wanted to dig deeper into getting more done with your time. I recalled reading Flow back in college. What stood out most was that you enter flow state literally changes your perception of time, and that it occurs when you have balance between the challenge and your skills.

Finally, to get more pragmatic, I recalled Deep Work, another book about focus that I’d read while working at Oracle. After a quick refresher, I had some practical and actionable steps to be more efficient with your time.

Doing well researched writing is like building with legos. The lego pieces are the notes you take from personal observations and primary sources. But there’s no instruction manual for connecting ideas together. That’s where you need to have a little creativity and vision to connect them into a cohesive narrative.

“Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something.” — Steve Jobs

Part 3 - How To Publish Quality Writing

As mentioned earlier, my initial struggle with writing was figuring out how to sit down to write consistently. Then, the struggle became conducting good research.

The final battle was consistently putting out quality content. The solution is simple, but not easy: Publish what you’re personally proud of.

A study from the 1920’s gave us the path to finishing high quality writing.

The Zeigarnik Effect

In the 1920’s, Bluma Zeigarnik, a Soviet psychologist asked participants to complete a variety of tasks. Some solved puzzles, while others worked on math problems. Half of the tasks were completed, while the other half were interrupted before they could finish.

An hour later, participants were asked to recall information about the tasks they’d worked on. Those who were interrupted had twice the recall ability than those who weren’t interrupted.

The phenomenon—now known as the Zeigarnik effect—is thought to be due to mental tension which keeps a task readily available in memory until it’s completed. This motivates the brain to actively recall and resolve it in the subconscious mind.

Strategic Procrastination

Have you ever rushed to get a creative project done? This might be because you’re finishing it too soon, not giving your mind time to work on it fully.

James Webb Young describes the incubation stage in the Technique for Producing Ideas as “where you let something beside the conscious mind do the work of synthesis.” Set the problem aside, and let your mind do the work of connecting ideas for you while you sleep.

“The more time an artist devotes to learning about an aesthetic “problem,” the more unexpected and creative his solution will be regarded later by art experts.”

— Sönke Ahrens

By leaving a writing project “on ice” for some time without hitting ‘publish’, your mind will subconsciously work on the project. Without realizing it, your brain will fill in gaps, add new ideas, and ultimately lead to a higher quality final product.

While incubation helps you develop an essay over time, the quality of what you incubate depends heavily on what you regularly consume.

Part 4 - You Are What You Read

Everything you write is a downstream output of all the information you regularly consume. Develop a taste for what author you want to sound like, and read more of them. Inevitably, you’ll write like who you read.

Peggy Noonan, Ronald Reagan’s speech writer, recommends that any young student read more. In her words:

“The important thing to tell a student entering college or high school: Read. Reading deepens. Social media keeps you where you are. Reading makes your mind do work.”

My friend Louis (what’s up Louis) said he’s been reading Thomas Merton lately. His most recent essay literally sounded like the Louis-version of Thomas Merton—in a good way.

Reading also expeditates your research process. Any time you read a well researched non-fiction book that you like, go into the notes section. Circle the sources that contained good ideas so you can look into them later.

“The most important advantage of writing is that it helps us confront ourselves when we do not understand something as well as we would like to believe.”

— Sönke Ahrens, How To Take Smart Notes

Part 5 - Integrate Knowledge Broady

To conclude this essay on how to write well, I’ll leave you with a quote from David Epstein, via his book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World:

“The bigger the picture, the more unique the potential human contribution. Our greatest strength is the exact opposite of narrow specialization. It is the ability to integrate [knowledge] broadly.”

— David Epstein

Epstein, and many others, agree that humans advantage over Artificial Intelligence is our ability to creatively connect ideas across domains.

Over the next decade we’re going to see the supply of writing increase dramatically. But those who can think clearly, synthesize meaningfully, and write thoughtfully will stand out more than ever.

Become one of them.

—Grant Varner

I’ve drawn a lot of inspiration from Ben Franklin. That’s why the profile picture of this blog is of Ben Franklin. Also because he’s long dead, and I figured there’s no way his ancestors would sue me for using an image of him on this blog.

Isaac Newton was thought to be a INTP Myers Briggs profile like myself, and for that reason, he is particularly inspiring to me.

The order in which I actually found these ideas may not be true, but the main point is that in Slumdog Millionaire fashion, I stumble upon, and capture good ideas over time to eventually use in my essays.

I loved this, Grant. I actually saved it for future reference because there is a lot of theory and mental models I can use for my own benefit.

Thanks for putting all of this together, I will definitely take a read on Smart Notes because that's an area in where I'm still learning.

Keep up the good work, you are rocking!

“Well”

I’ll see myself out…